An explanation by Ray Mills, a 78-year-old, Forres born, volunteer from the Forres Heritage Trust.

History, like politics and religion, is a very subjective matter, very much a question of how you see things with your own eyes in real time, or as envisaged using your own imagination, looking back through the mists of time immemorial. Sometimes the clues to understanding history are very well hidden, but sometimes they are also hidden in plain sight.

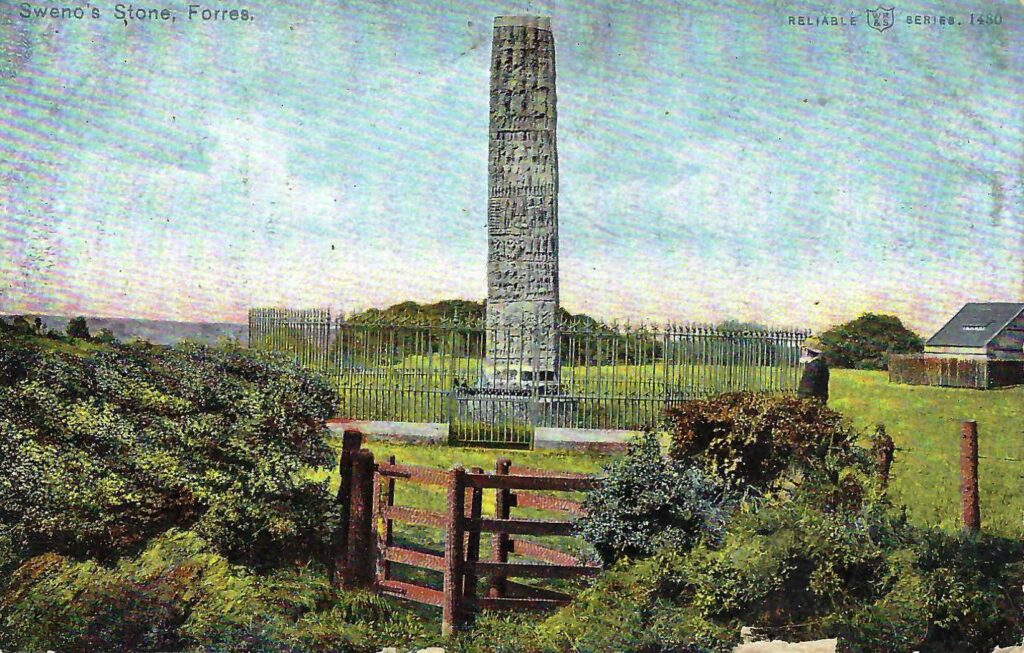

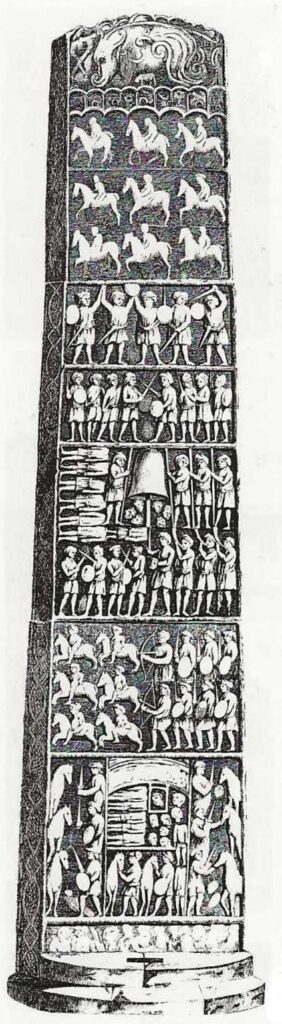

For hundreds of years, historians have postulated their various theories as to what the carvings are all about on the Stone of Forres, that ancient obelisk now commonly, and mistakenly, known as Sueno’s Stone. This Pictish style sandstone cross-slab, at 23 feet the tallest in the country, is situated on the north east side of Forres in Morayshire, on what was once the B9011 road to Kinloss. Who made it, when, and why, has never been answered satisfactorily. The symbolism used on the Forres Stone is quite different to other stones, so mystery has surrounded any interpretation. Did it depict a victory for the Danes over the Scots, or the Picts over the Danes? Not likely. Did it depict a victory for the Dal Riada Gaels over the Picts? Maybe. Did it depict a triumph for Christianity over warfare? Most definitely.

As with any puzzle, one often has to look at a number of sources, and read a lot of different, often contradictory, reports, before a conclusion can be reached. And, as always with such matters, because of a lack of proper objective evidence, visual, verbal or documentary, any conclusion reached cannot be proved or disproved, so basic belief itself takes on much greater importance. After 70 years of such reading, I think my explanation below is believable.

One hundred years ago, in 1924, there were six churches in the town of Forres, all with sizeable congregations who practised their religious beliefs in buildings of outstanding build quality and architectural beauty. A hundred years later, in 2024, these churches are now reduced to three in number, and struggle just to fill one. How things can change in just a hundred years. Perhaps it is all down to communication, and different forms of communication. People love stories and symbolism, to learn things, and throughout history the Christian church in Scotland has been a key communicator to the people.

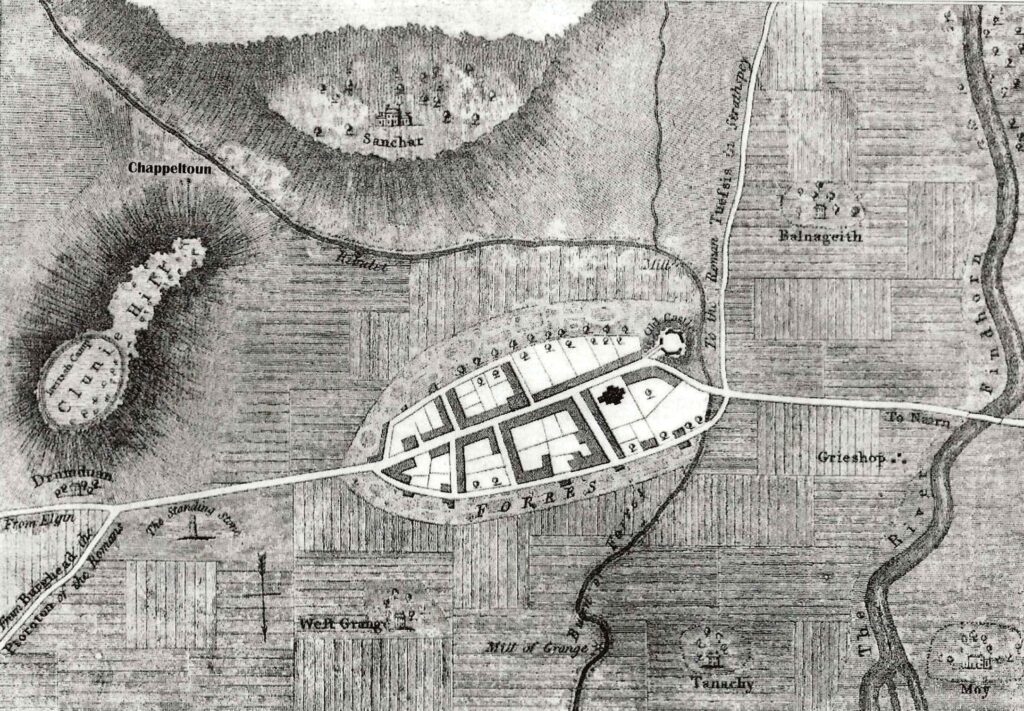

Imagine then, how things could have changed from almost twelve hundred years ago, when communication about any major event was at a completely different level, with hand carved stones for the many and hand scribed vellum for the few. If we can go back to 843AD, the year when Kenneth MacAlpin founded the first state known later as the Kingdom of Scotland (Alba), there was at that time, only the one “church” in the Forres area. This wouldn’t be a church as we know it, more like an ecclesiastical settlement, a muinntir, with a central meeting place, probably made of wood, wattle and daub, and a roof of thatch, surrounded by a few monastic cells for its religious inhabitants. Their central place of worship was a comparatively humble building, probably about 50 feet by 20 feet, erected at a spot now known as Chapelton, just outside of town, on the elevated south east side of Forres. Its influence must have been held in quite high esteem, because seven hundred years later, the name still appeared, in sizeable print, as “Chappeltoun”, alongside “Shancharr” (Sanquhar), on Timothy Pont’s map of 1593 AD (appendix 1), and copied later on Johan Bleau’s map of 1654 AD.

This Chapel community housed devotees of Saint Mael Rhuba (642 AD-722 AD) the Irish saint who, as a 29-year-old Christian missionary, had arrived at Applecross on the west coast of Scotland, coming over from Ireland in 673 AD. He made Applecross the nucleus of his missionary work which extended right across Scotland, like St Donan and St Columba before him, and St Ninian before that.

Christian sites like Applecross, and Iona, were run by monastic devotees, monks who were skilled in many ways, including stone sculpture. The Culdees (from Ceile Dei – Servants of God) were an early cult of ascetic Christians who had many sites around Scotland which greatly influenced the local populations, as well as their leaders, whether they be Kings, Mormaers, Nobles, Earls, Thanes or some other nomenclature indicating chiefdom of the main areas that Scotland was divided into. The Chapel at Chapelton in Forres, was established and run by Culdees, who had links to other Culdee places like Keith, Rosemarkie, Nigg, Hilton, Portmahomack, Loch Leven, Dunkeld (Fort of the Keld), and Scone, places where similar stone sculptures have emanated from. Culdee worship at Scone is believed to have been established as early as 700 AD. These were devout holy men who loved solitude and lived by the labour of their hands. They came together as a community, but still lived in separate cells. They lived a life of contemplation, work, prayer, scholarship and learning.

It is uncertain when Christianity was first known in Forres. There would be no clear line of demarcation between the Druids, and the establishment of the Culdee Church. One decayed as the other flourished. Certainly, by 800AD, most of the Pictish world, including Forres, would have adopted Christianity. When the heathen Norsemen raided Iona for a second time in 806AD, and the entire community of 68 monks was murdered there, a paradigm shift occurred. Over time, the ecclesiastical centre was gradually moved from Iona to Dunkeld. The Stone of Destiny, the traditional coronation stone of the Kings of Dal Riada, and later Scotland, was moved to Dunkeld then to Scone. These moves to South Pictland, born out of necessity to provide protection against a common enemy, paved the way towards the union of Picts and Scots. These were two peoples who were by now of the one faith.

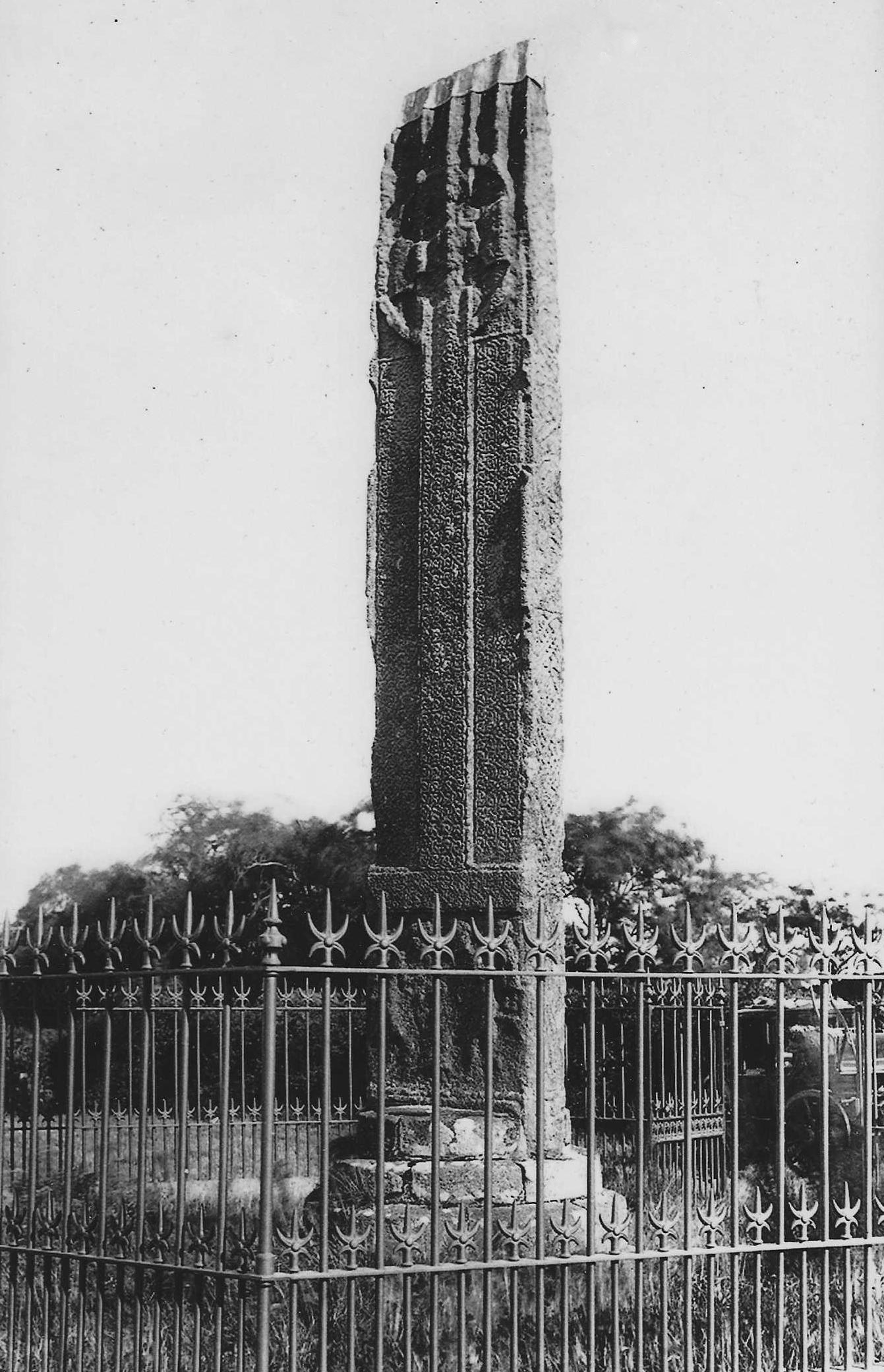

The most important symbol in Christianity is the Cross, the Cross on which Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews, Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, was crucified. His death and resurrection are fundamentals of the Christian faith. On the Stone of Forres, the largest piece of sculpted symbolism that is communicated to us, is the seventeen foot high Cross, which takes up almost all of the west face of the Stone.

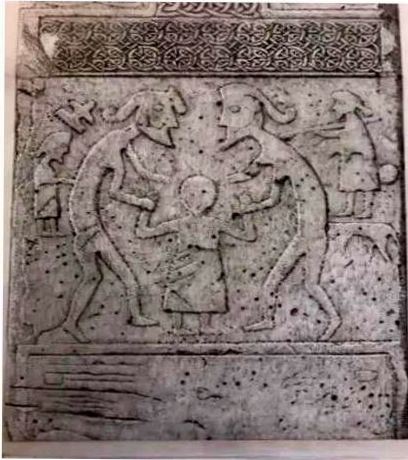

With a small panel below it, depicting a coronation, or a kingly succession scene.

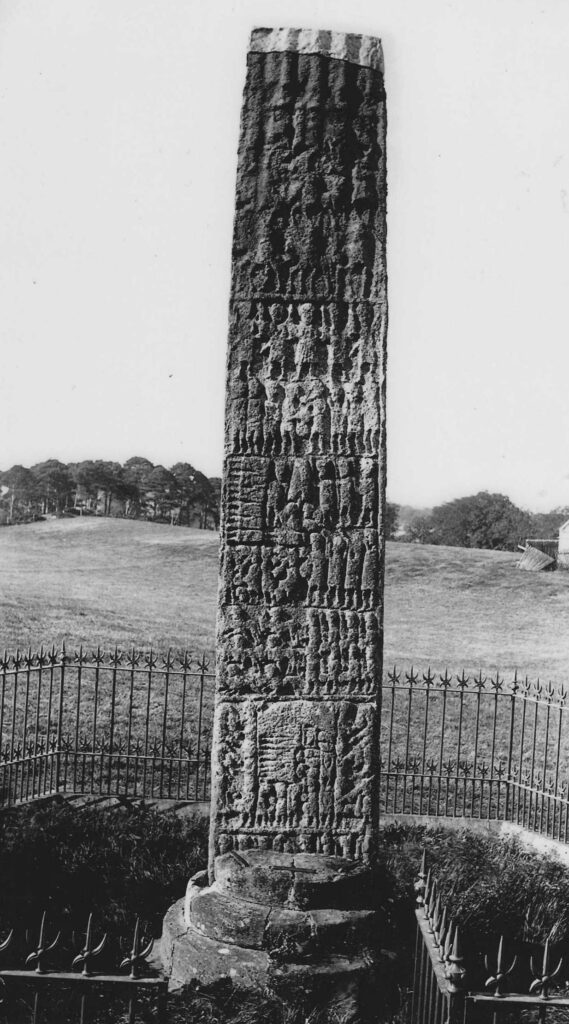

Because of the mystery of all the other imagery, depicting military might, battles, victories, executions, (appendix 5 and 6) we are blindsided to the most important message of the stone. The monks at Chapelton knew that the only real King worth fighting for, was our Lord Jesus Christ, not any of the other Pretendres who constantly involved themselves in warfare of one kind or another, as depicted on the six main panels on the east side of the stone. If the one side of the Stone is alive with the drama of war, the other exhibits, in boldest relief, the Christian emblem of peace and goodwill.

Whether these warmongers were Picts or Scots, was of no consequence to these true followers of Christ, but to the leaders of these warring peoples, awareness of the ever-increasing unifying influence of the Christian faith on the country, had to be well considered and taken on board. The influence of these St Mael Rhuba devotees in the Forres area was very strong. It was strong enough to enable, at the behest of the new King Kenneth MacAlpin, the mining (at Clashach), the movement, the sculpting and the erection of this enormous seven-ton stone slab, with its ten-ton subterranean foundation, to act as a permanent message to the population of the wider area of Forres, which was at that time of prime importance in the lush farmlands and forests of this part of North Pictland (appendix 7), or Fortriu, as it was known back then.

The antiquity of Forres goes back at least as far as the first century AD, when the Vacomagi had a hill fort on what is now Cluny Hill. At the time of the Roman general Julius Agricola, and the battle of Mons Graupius in 83AD, it was known as Varis. In 535AD it is recorded that Forres was a “town” with merchants who were accused of treason by the provincial king’s chancellor, and some of them were subsequently executed.

Since the sixth century, Forres had been the most important market place in the north of the country. It had a very strong merchant base and did considerable trade with other ports around the coast, and perhaps even across the North Sea to Norway, Denmark and the Baltic. Because of this commercial and political importance, Forres had royal associations for centuries and was the royal centre of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. The Annals of Ulster record a battle in 839AD between the Gaels and Picts combined against the heathen Vikings, somewhere in Fortriu, and that place probably was at Forres. There were major losses in the conflict, on all sides, although the Annals say the heathens won. Was the first Castle of Forres burned to the ground by the Vikings at that time? We don’t know for sure. We do know from the Annals of Ulster that King Eogan and his brother Bran (sons of the Pictish King Onuist of Fortriu) and King Aed (son of the Gaelic King Boanta of Dal Riada) were killed in this battle. Into the resultant power vacuum, a Gaelic warlord called Alpin emerges, supported by two of his sons, Kenneth and Donald, and he somehow manages to take over the leadership, and probably the kingship, of Dal Riada. Two years later in 841AD, Alpin died and was succeeded by his son Kenneth, who moved into Pictland. Kenneth moved his royal centre from Dal Riada to Forteviot in South Pictland, but he knew he must consolidate his position in the North as well. Forres in Fortriu in North Pictland was still regarded as the centre of a recalcitrant province where he needed to improve his authority and popularity. Kenneth MacAlpin, ever a man with an eye on the main chance, came in with his army from Dal Riada and drove out the remnants of the Danish forces and he took control over the Picts, who offered little resistance. In 841 AD he brought the sacred Stone of Destiny from Iona (where he was born and where ultimately he was buried) via Dunstaffanage and Dunkeld then to Scone, and the Culdee church there took on much greater significance. In that same year, Kenneth MacAlpin invited the Pictish King, Drest (nephew of Onuist) and seven of the Pictish nobles to come to Scone, to discuss the Tanistry lines of succession to the Pictish throne, as Kenneth had a vested interest in this through his maternal lineage. At the ensuing banquet, much alcohol was consumed, and the Pictish King and his nobles were subjected to a horrific fate. Being in a drunken state, they fell from their seats when MacAlpin’s men removed the bolts that supported the seats, and the Picts were then murdered in the traps that they found themselves in. For sheer perfidious ruthlessness and cunning we should replace Machiavelli in history, with MacAlpin. MacAlpin then had little opposition in taking control, and in 843AD, unopposed, he was crowned the first Gaelic King of Picts, in Scone, anointed as was Gaelic tradition with holy oil under a Canopy, while seated above the Sacred Stone that he had taken over from Iona two years before.

It is important to look at MacAlpin’s achievements in the context of the wider world he lived in. Just 43 years before MacAlpin’s coronation in South Pictland, King Charlemagne of the Franks had been crowned, by Pope Leo III in 800AD, as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, a huge area which Charlemagne had expanded by brute military force, covering France, Germany and most of Italy. Charlemagne then sought to establish a new standard of law and Christian enlightenment for all the people of his empire. He even moved the religious centre from Rome to Aix-La-Chapelle (Aachen), making it a royal centre also. Kenneth MacAlpin perhaps sought to emulate some of the achievements of this hugely influential historical figure, who died in 814AD.

Being all powerful now, controlling Dal Riada, as well as North and South Pictland, MacAlpin wanted to tell the world in a convincing way, what had happened. And so it was at Forres in 844 AD, that he commissioned the Chapelton Culdees to make a monolith which communicated to the world, the execution and beheading of his enemies, with a Bell, the symbol which traditionally represented the public announcement of any deed, and a Canopy which represented the sacred anointment with holy oil, of a new monarch. The coronation panel below the Cross, showed that future kings would be as Kenneth MacAlpin wanted, but never actually got, through primogeniture (first born legitimate male succession) not the old Tanistry system of succession through two closely connected family lines. Ideally, he wanted a single line of descent, a line with Royal blood, anointed by God. He wanted any future Royal succession to be a peaceful affair, free from the usual associated bloodshed of the past. Here was a warlord with a conscience. The message that was now being affirmed on this tablet of stone was his conquest of Pictland, and his Christian overkingship of the realm that was to be at a later date known as Scotland (Alba). This was more than just uniting the Scots and the Picts. This was a warrior aristocracy uniting with the Christian church, to become an even more powerful force. This was a message very much of national importance.

It was Kenneth’s intention that after their coronation in Scone, all subsequent Kings of Scots, would come to Forres, to be accepted by acclamation at this magnificent monolith. This they (and their followers) did by the ritual drawing of their swords (not sharpening, more acquiescent blunting) across the base of the west face of the Stone, at the bottom corner of the coronation panel below the Cross. This practice had been started in ancient Irish Gaelic royal affirmations, with similarities to the stones at Kilsnaggart in Co Armagh, the Cross at Kells in Co Meath, and the Mullaghmast Stone now in the National Museum of Ireland. It was seen as denoting allegiance to a higher order, our Lord Jesus Christ, and an affirmation of a commitment to being a Defender of the Faith. It symbolised the returning of the power of the sword back to the Cross of Christ, by a rightful and just King. It is quite ironic that in later years these sword marks on the Forres Stone (appendix 8) were reported as appearing to be nothing more than intentional defacement and disfigurement, akin to vandalism, and the meaning of their original purpose was lost to posterity.

It has been suggested that the marks were made much later than the time of erection, by workmen sharpening their axes, sickles or scythes. I believe that these are tools and implements which are best sharpened by using an individual handheld whetstone. I have conducted experiments by drawing a steel blade across hard yellow-grey sandstone, and concluded that any ritual drawing by a King and his retinue, with hundreds of followers performing the same action, would leave similar indentations (appendix 9). They would draw their sword blades in a sawing motion across a slot, with an initial guide groove hewn by a stonemason’s hammer and chisel. What words they repeated during this ritual we will never know, but they were undoubtedly about swearing allegiance to their God and to their King.

It is worth noting that during the 2023 Westminster Coronation, three silver gilt swords (other than the Sword of State and Sword of Offering) were carried by Peers of the Realm in front of the King and Queen, each representing an aspect of the King’s powers and duties. The Sword of Temporal Justice represented the King’s role as Head of the Armed Forces, the Sword of Spiritual Justice represented his role as Defender of the Faith, while the blade on the sword “Mercy” was blunted to symbolise that the monarch should be merciful.

The synergy is obvious and intense between the Stone of Destiny (Jacob’s Pillow) the Stone of Scone, on which Scottish Kings were seated and crowned throughout history even up to the present day, and the Stone of Forres, where they were affirmed after coronation, a practice which stopped at some later date. Despite what King Kenneth the First had hoped for, only ten Kings (Kenneth I, Donald I, Constantine I, Aed, Giric, Donald II, Constantine II, Malcolm I, Indulf, and Duff) were affirmed with the sword ritual at the Stone of Forres, as borne out by the ten groove marks on the Stone.

The MacAlpin dynasty it turned out, was not so very popular in the Forres area and at least three of his descendants met with a brutal demise while in the vicinity of Forres. They were, his grandson King Donald II (889-900), his great grandson King Malcolm I (943-954), and his great great grandson King Duff I (962-967), who all suffered fatally at the hands of Moray men. The Ulster Annals also record that even Kenneth’s son Aed, who reigned for only a year, 877 to 878AD, was killed in “civitas Nrurim”, which no one has identified, but I would suggest that this is Nairn, just ten miles from Forres. After these deaths, not unsurprisingly, the ritual was stopped. Kings Cuilen, Amlaib, then King Kenneth II (971-995) the son of Malcolm I, and the great, great, great grandson of Kenneth MacAlpin, thought that it was not very sensible to carry on with such a tradition, and it was abandoned about 120 years after it had begun. By the time that ten more Scottish Kings had been crowned at Scone (Cuilen, Amlaib, Kenneth II, Constantine III, Kenneth III, Malcom II, Duncan, Macbeth, Lulach and Malcolm III) the tradition at Forres had been well and truly consigned to history. It is recorded that King Malcolm III saw the Stone during a military campaign up north in 1060 AD, and he thought that it had been erected by the Danes, so little was it understood by that time.

Thirty years after that sighting, and 240 years after it was first erected, still in the reign of King Malcolm III in 1091AD, the Stone of Forres fell over during a ferocious storm (a tornado being recorded in London that year with extensive damage). It became buried, and thereby was preserved for nearly 500 years, in the shifting sands (of Culbin) that surrounded this area, and then later it was re-erected, but it was never again used for its original purpose.

Regarding the date of re-erection, we do know that it was before Timothy Pont’s map of 1593, which shows a graphic of standing stones. We also know that in the intervening years, King Edward 1 of England visited Kinloss Abbey in 1303, and later his grandson King Edward III of England also visited the Abbey in 1336. If either of these two Kings had seen this mysterious Christian monolith at the side of the road on which their horses were travelling, on their way from Forres to Kinloss, they no doubt would have removed it to Westminster Abbey in London, just like the Stone of Destiny was taken previously by that same King Edward I in 1296, after the abdication of the King of Scotland, John Balliol.

In 1527, the historian and the first Principal of Aberdeen University, Hector Boece, published the first printed book solely dedicated to the History and Chronicles of Scotland. Boece is famous for his inaccuracies, but there are facts aplenty in his work. This book, written in Latin and translated 10 years later by John Bellenden, Archdeacon of Moray, mentions “Sweno” and “Fores”, but not the Stone which had not been re-erected at that point in time. Alexander Gordon then in his 1726 Itinerarium Septentrionale, associated the Stone of Forres with Sueno, for the first time. The National Library of Scotland has nine original copies of Boece’s book, and one of them is signed by Thomas Randolph, who was the English ambassador to Mary Queen of Scots.

Perhaps it was the 19-year-old Mary Queen of Scots, accompanied by her half-brother James Stuart, while on a visit to Forres and Kinloss Abbey, on 8th and 9th September 1562, who found out about this uncovered Stone and covertly funded its re-erection. Although staunchly Roman Catholic, and not a supporter of Culdee Christianity, she learned from the now Protestant monks at Kinloss, about the political importance of the stone. Since it had been erected for the first King of Scots, and she being the first Queen of Scots, it made sense to have the Stone re-erected. Because this was a time of ongoing major conflict between those factions, John Knox et al, who were reforming the religious landscape, and the issues from politics and religion being so finely balanced, she did not want this act to be held against her. After her visit to Kinloss Abbey, she then spent a day with James Stuart at his Darnaway Castle, where a tournament was organised in her honour, this to take place after a Council of State.

This tournament was very similar to one held 170 years previously, in May 1390 AD (a painting of which hangs in the Tolbooth of Forres). At this earlier tournament, an invitation to compete had not been forthcoming for Lord Alexander Stuart, the Wolf of Badenoch, because he had been ex-communicated from the Church, and so, in a fit of indignation, the Wolf went on the rampage and destroyed by burning, the Archdeacon’s Manse in Kirk Vennel (Gordon Street) in Forres, along with all kinds of historic documentation, no doubt including details of the Stone of Forres. The Stone had been buried for almost 500 years of its history, and while this had helped to preserve its sculpture, it had clouded its original meaning and purpose.

Then, 130 years after it had been re-erected in the 1560’s, the Stone once again moved precariously, but it did not fall to the ground. This happened at the time of the devastating storm which covered the Culbin Estate in 1698AD. Leaning over, it was subsequently reported as having been “like(ly) to fall”. This was reported in later accounts, firstly by Alexander Gordon in 1726AD, and then Rev Lachlan Shaw in 1775AD. Fortunately this situation had been rectified sometime between 1700AD and 1725AD, by Lady Anne Campbell, the Countess of Moray, who ensured it was positioned upright, and steps built around its base, thereby preventing it falling over again. Lady Anne Campbell was married to Charles Stuart (1660AD-1735AD) the 6th Earl of Moray, who was a direct descendent of James Stuart, the half-brother of Mary Queen of Scots. If my assertion about Mary’s involvement in the re-erection of the Stone is correct, then the Stuart family deserve a great deal of credit for the survival of the Stone, and its part in the local heritage.

With regards to the Chapel at Chapelton, commemorative celebratory annual “Samareve” fairs, named in remembrance of St Mael Rhuba, were held every year on his feast-day (August 27th) in the wealthy market town of Forres for over three hundred years. Fishing, farming, and forestry, were always the mainstays of the local economy, and were very lucrative for the powerful landowners who supported this Christian enclave. The advent of the Cistercian Abbey at Kinloss, in 1150 AD, and the Royal seal of approval by King David 1 that was given to that establishment, undoubtedly diminished the power of the Chapelton religious order, although it survived into the 17th century. About 1275 AD, the Chapel at Chapelton was dedicated to St Leonard, in line with the established church, and St Mael Rhuba, as well as the Culdees, became a distant memory. The south road leading from the town to the area where the chapel once stood, was formerly called St Leonard’s Road, then later renamed as Bulletloan, and then in relatively modern times, in September 1890AD, it was again renamed St Leonard’s Road, and this is the name it still holds. A local historian reported in a Forres Gazette of 1910AD, that St Leonard’s Road actually had no claim to that name, as the original public right of way used to pass through Applegrove, then over Breakback (which it still does), along the Mosset burnside, and then up to the Chapel. It is very likely that both the pathway and the road co-existed as routes to the Chapel, for centuries.

Prior to the introduction of piped water to the town in 1845AD, potable water was drawn or pumped from a number of wells, fourteen of which are described in the Annals of Forres. One of these wells was located near the bottom of Cumming Street, at the path across Applegrove, and it was known as St Malruve’s Well, another indication of that Saint’s connection to the town.

This early monastic order at Chapelton predates by 450 years the first Chapel of St Laurence in Forres, which was built in 1275 AD, at the instigation of King Alexander III, with prayers to be said for the soul of his wife Margaret. Her Romanising influence on Scottish Christianity was immense, thereby initiating a movement against the Culdees. The Chapel of St Laurence was built on the north side of the main street (appendix 10) along from the site of the Forres castle(s) based at the west end of the town, and this is where the present St Laurence Church is now situated. St Laurence then became the Patron Saint for the town.

The Chapel at Chapelton was recorded as still being in use in 1337 and again in 1456. King James IV on one of his progresses around the country, made a donation to the Chapel in 1505. By about 1550, this Chapel (perhaps the fourth Chapel building to have been at this site) was becoming ruinous, and it was replaced by a (fifth?) newly erected Chapel of St Leonard in 1612, when it was recorded that “Patrick Tulloch of Tannachy was presented”. This Chapel also eventually fell into disrepair and was abandoned. Some 270 years later in 1880, there were still some small traces of the foundations and the adjacent burial site, but today there is no evidence whatsoever left of any of the Chapels’ existence.

However, the twenty-three foot tall, grey blue sandstone pillar, that was so artistically produced by the hands of the Culdee monks of Chapelton, on the orders of the reigning monarch, King Kenneth the First, still stands proudly on the old Kinloss Findhorn Road, at a spot close by to the old town boundary. The Stone of Forres is now entirely covered in with strengthened sheeted glass, to protect it from the elements (appendix 11).

To this day, it still proclaims that “Christ is King”. The Stone of Forres should now be recognised as a nationally important pilgrimage point for all believers, whether these be royals or commoners. It should be a shrine, a sacred place, where people of every colour and creed can say a prayer for peace in this troubled world.

Notes:

Note 1; The twin pillars shown north of Forres on the Timothy Pont map identified in this text are not proof of the existence of another stone like the Stone of Forres / Sueno’s Stone. Pont used the graphic of two standing stones for any site where there were standing stones, whether it was one single stone, or a circle of stones, as shown on other maps that he drew.

Note 2; On the east side of the Stone, there are nine separate panels, as follows;

- An elephant headed emblem, above a wolf.

- Nine emblems, in scalloped edging.

- Nine men on horseback, in three rows of three.

- Five men with swords, and shields raised in celebration.

- Eight men, three either side of two in the middle, who are fighting.

- Seven headless bodies, six heads, a Bell, four men with spears, five men with swords and shields, four fighting are smaller than the fifth, and three men with trumpets sounding.

- Six men on horses, three rows of two. Two archers with bows and arrows. Six men with swords and shields.

- Seven headless bodies, eight heads with one of them in a box, a Canopy, eight horses, eight men with swords and shields, a hanged body.

- An assortment of human torsos.

Note 3; There are interlaced knot carvings all around the outside edges of the Stone. At the bottom of the east edge there are images of women holding hands.

Note 4; On the west side of the Stone, there is only the Cross and circle decorated with interlaced knots, above a coronation panel. The coronation panel has two bearded men, one on either side holding the raised arms of a kilted/frocked/robed child, and behind them are two other men. One has a crown above his head, the other carries a spear, and is above a wolf, the great enemy of the Shepherd. It may be worthy of note, that the tonsure style of these bearded men of the Church hierarchy, looks like the Iona Celtic fashion (entire forehead shaved back to the ears) rather than the circular coronal tonsure of the Roman Church. Along with the computing of an agreed date for Easter, this tonsure fashion had been a major area of contention, and therefore division, between the Christian institutions. It was supposedly ratified at the Synod of Whitby in 664AD, but not everyone complied. The Celtic Christian community were perhaps slow and reluctant to accept Roman Catholic ways and customs, but their differences were never theological, and their beliefs were always orthodox.

Some historians say that this panel cannot represent a coronation scene, as they believe kings were not crowned at the time of MacAlpin in Scottish history. Perhaps they say this mostly because there is no contemporary depiction of a crowned Scottish King until the Great Seal of King Edgar (1097-1107AD). I would counter this by saying that just because there isn’t a picture doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. We must bear in mind that the English King Egbert (827-839AD) was crowned, pre- MacAlpin, in Wessex, after returning from exile at the court of King Charlemagne, a king who certainly was in favour of wearing a crown. Also, in the Royal Collection Trust’s Great Gallery in Holyroodhouse, there is an oil painting by the Dutch master Jacob de Wet II, which depicts Kenneth MacAlpin with a crown by his side, and there is no reason to doubt his research for his series of Royal paintings in 1684.

Note 5; For many years historians have wondered about the locations of the ancient Pictish provinces of Cait, Fidach, Fortriu, Ce, Fotla, Circind and Fib. Fortriu, especially, is important, as it was mentioned in the Annals a few times, including the major battle of 839AD. Alex Woolf has proved beyond reasonable doubt that Fortriu was in the Moray area, although part of his argument was based on the name Invererne, a farm estate in Forres. In the Annals of Forres, Robert Douglas states that this name Invererne was a relatively recent name change, as it was previously known for centuries as Tannachy.

Note 6; The actual location of the demise of King Donald II (889-900AD) has also been contentious to historians over the years. Alex Woolf and others say that this happened at Dunnottar. WF Skene and others say that this happened in Forres. I agree with Skene on this.

Note 7; Some historians have made reference to the Stone of Forres being moved from another site at Alves, where there were standing stones, including the “Lang Stane” that was moved by the Gordon Cumming family to Altyre. For many years it was assumed that the Forres stone was at least 11 feet buried into the ground to be able to support its height of 23 feet above ground. However, excavations at the site in the 1920’s have proved that the stone is actually slotted into a channel of about 15 inches in depth, this channel being in a massive foundation stone of about 10 tons in weight, so the Stone stands in its original position. There is no evidence of there being another 10 ton foundation stone to support a second stone, as mentioned in note 1. Additional post holes used for erecting, found during Rod McCullagh’s excavation in 1991, were used for re-erecting the stone, not for erecting a second stone. I believe that the results of latest carbon dating technology (825-885AD, 68% probability) do not conflict with the timescales and dates of my findings.

Note 8; Originally when erected, the Cross side of the Stone had faced towards the morning sun from the East, to be viewed in a blaze of glory. But during that 1091AD storm, the prevailing wind from the West had blown the Stone over so that the Cross side was facing down, and when re-erected this face was wrongly placed, unfortunately now facing West.

Note 9; Is it just coincidence that the four following stones were all erected in a straight line along the Moray coast; the Keppuch Stone, the Achareidh Stone, the Dyke Stone, and the Forres Stone?

Note 10; In February 1802, there appeared in a number of newspaper publications including The Aberdeen Journal, the London Chronicle, the London Star, and the Lancaster Gazette, an article which referred to an inscription (on the Stone) of ten initial letters (LOHHINRESI) which no antiquarian had ever taken note of. This was then translated by an un-named expert, who explained that the Stone was connected to the driving out of the Danish King Sueno from this land. Since the inscription was supposed to be initial letters only, and these could not be identified anywhere on the obelisk, the report would appear to have been considered unreliable, but this may have further reinforced the reason for it being called Sueno’s Stone. The historian James Bruce has recently highlighted that these articles appeared in the Press just weeks after the famous Rosetta Stone had arrived at Portsmouth from Egypt, and the decoding of ancient stelae was very much in vogue.

Note 11; The Stone of Forres is located at a spot, exactly a mile due north of Chapelton. This spot is also just a few paces from the old Forres town boundary, which was marked by the Little Market Cross (not to be confused with the Market Cross at the Tolbooth in the middle of town). Boundary markers were always good assembly points for making public announcements. For centuries the Little Market Cross, and the adjoining Toll Cottage, was the place where tolls (taxes) were extracted from visiting merchants who had come to sell their wares. The pedestal foundation for the Little Market Cross still stands, although it is hidden behind a garden wall, at Rosefield. It is possibly the second oldest carved stone in Forres’ history.

Note 12; The Stone of Forres lies on land which for centuries was owned by the Stuarts of Darnaway/ the Earls of Moray (Moray Estates). Chapelton lies on land which for centuries was owned by various families as lairds of Sanquhar Estate. Archaeological surveys have taken place at both sites, but very little has been uncovered or proven at Chapelton, perhaps due to the location of the field visits (with no geophysicals, or trial trenching) in the 1960’s and 2000’s. Wright’s Hill maybe a good site, and the adjacent fields show shading in aerial views, which may be evidence of an enclosure (see Appendix 14). It is not known if any surveys were performed on these areas relative to a new golf course development, proposed by Sir William Gordon Cumming and the Altyre Estate Trustees in 1991. The area known as the Haugh or the Monks’ Field (see appendices 12 and 13) lies in an area which is now controlled by the Forres Friends of Woods and Fields Trust (chairman, Nick Molnar) with path access partly controlled by Forres Community Woodlands Trust (chairman, Don Wright), so their assistance and co-operation in any future archaeology is imperative. In fact, support from the whole Forres community is needed. And possibly the Scottish community, the United Kingdom community, the European community, and the Global community too. Finding evidence of a 9th century ecclesiastical settlement at Chapelton, is critical to my argument about the Stone of Forres. Anyone who senses the otherworldliness of this idyllic Chapelton location, with the Mosset Burn, Forres’ life source, meandering alongside, will fully appreciate why the first early Christian missionaries would want to live here.

Note 13; From the Decrypt Project, we know since February 2023, that three amateur codebreakers, one from Germany (Nurbert Biermann, musical coach), one from France (George Lasky, computer scientist), and one from Japan (Satoshi Tomokiyo, patent expert), have deciphered using artificial intelligence and computer algorithms, 57 letters written in code by Mary Queen of Scots between 1578AD and 1584AD. They were stored (mis-filed through ignorance of the contents) in the National Library of France, in Paris. Since there are a number of her other coded letters still to be worked on, perhaps one someday may shed light on the Stone of Forres and her involvement in its re-erection.

Note 14; Provost Forbes in his 1975 book “Forres; A Royal Burgh”, mentions a full-scale replica of the Stone of Forres. This was made by the Ministry of Works for the 1951 Festival of Britain celebrations, held on the South Bank of the Thames. I thought that it would be fantastic if this was found, and erected in the Forres Falconer Museum, which really should be re-opened as soon as possible. Recent inquiries made to the Southbank Centre Archives indicated that they do not have the replica. They suggested trying the National Archives at Kew. Research of their archives indicated only the existence of a photograph of the replica, not the replica itself. However as luck would have it, in May 2024, I found in my archives, two negatives of the original photographs taken by my father in April 1951, of the cast being made by John Mackenzie, a master craftsman from Edinburgh. It turns out that the cast was exhibited in Edinburgh, as a regional centre for the Festival of Britain. Contact has now been established with the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh (Martin Goldberg) who has confirmed that the cast is in too delicate a condition to be moved, let alone displayed, but has offered access if required. Martin intimated that the last interaction with these casts was the HES illustrator John Borland, who made scale drawings of the monument.

Note 15; As stated earlier, the synergy is obvious and intense between the Stone of Scone and the Stone of Forres. The first ceremony in which the Stone of Destiny was used at Scone was the crowning of Kenneth MacAlpin in 843AD. The last ceremony in which the Stone was used at Scone was the crowning of John Balliol in 1292AD. In the 450 years spanning these two Kings, there were 30 Kings crowned at Scone, all seated above the Stone of Destiny. Whether they were all anointed with holy oil under a canopy (that holy sacrament which emphasised the spiritual status of a sovereign and considered to be a sacred mystery) we can’t be sure of, because of a lack of surviving records. Many historians believe that the earlier ceremonies, including Kenneth MacAlpin’s, would have been pagan and performed with minimal religious references. Some believe that this was the case right up to King Robert 1, who finally secured in 1329AD, through a Papal Bull, the rite of unction for Scottish Kings, and so David II (Robert’s son) became the first Scottish King to be crowned as well as anointed (so they believed). Some historians argue that because it is recorded that the earlier Kings, Duncan I and Macbeth, had to apply to, and were refused by, the Pope in Rome, for permission to use “holy oil”, then the anointing ceremony under a canopy could not have happened prior to that. They assume therefore that the image on the Stone of Forres cannot be an anointing canopy. The Gaelic King Aedan of Dal Riada is recorded as being anointed at Iona by St Columba in 574AD. Therefore, I believe that Kenneth MacAlpin and his early successors were indeed also anointed with holy oil, although this oil was not sanctioned by Papal authority. These Kings were certainly not pagans, they were Christians, and the ritual that they performed at the Stone of Forres was also a Christian ceremony. Their Christianity may have been more Culdee Church than Roman Church, but it was certainly Christian none the less. Like the rider carved on the Pictish stone of Bullion in Angus, their celebrations may have been with local beer rather than fine wine from the Roman world, but celebrations they were, none the less. In 906AD there was a Church Assembly held in Scone under King Constantine II and Bishop Cellach, and there were absolutely no Papal legates in attendance. That absence (or exclusion) of Roman influence is important in any understanding of the culture at that time, attempting to decree that “the laws and disciplines of the Christian faith…..should be in conformity with the Scots”. During the next two hundred years however, Christianity under Papal authority, was to became of supreme importance to the Church and to the State, and the decline of the influence of the Culdee Church, including the Culdees at Chapelton, was underway.

The Stone of Destiny was kept for 700 years, since 1296AD, at Westminster Abbey, before being returned to Scotland in 1996AD. Early in 2024AD, it was permanently moved from the Crown Room at Edinburgh Castle, to the City of Perth’s new museum, near Scone. Perhaps now the relationship between the Stone of Forres and the Stone of Scone will be given the prominence it truly deserves.

Note 16; Regarding the origins of the Stone of Scone and the authenticity of the stone currently in Perth Museum, many conspiracy theories have been suggested. These include that it was once used as a doorstep, or was a building block from Antonine’s Wall, or a facsimile made by the monks of Scone Abbey to fool King Edward I’s English army in 1296AD, or even a cesspit lid which the Scone monks substituted for the real thing.

Although lithologically similar in structure to the Lower Old Red Devonian sandstone from the Quarry Mill near Scone Palace, the Stone of Scone has historically, like the Stone of Forres, been the subject of a misnomer.

The Stone of Scone could just as easily have been called the Stone of Dal Riada, or the Stone of Iona, places where the Stone had been used previously. As well as being similar to Scone area sandstone, electro-fluorescence will show that it is also similar in geological structure to sandstone from the Oban area, which was originally part of Dal Riada. It was certainly used for centuries for the inauguration of the Dal Riadan kings at Dunadd and Dunstaffnage.

In 563AD, St Columba established Iona as the main Christian ecclesiastical centre in Dal Riada. Eleven years later, in 574AD, the Stone was taken to Iona by St Columba, for the inauguration and anointing of the Dal Riadan King Aedan. And there it remained in Iona for subsequent Dal Riadan inaugurations (all records of which have been destroyed) until Kenneth MacAlpin removed the Stone to Scone in 841AD, for his own inauguration as the King of Picts and Scots in 843AD.

Although originating in Dal Riada, it was almost certainly a part of St Columba’s Christian ideology to link the history of the Stone of Destiny back to an ancestry in Ireland (home of the original Dal Riada) and thereby an ancient lineage back to Spain, and Egypt, and the Holy Land before that. This is totally understandable, as this was the route that Christianity originally took to eventually reach the people of what is now Scotland.

It is worth noting that as part of the early inaugurations in Dal Riada, each successive king fitted his foot into the carved footprint in the bedrock atop the pinnacle at Dunadd, symbolically making a gesture of preserving the ancient customs of their forefathers, and connecting with the land they depended upon. The Stone of Scone has a level of wear evident on its top surface that indicates it could also have been subjected to a similar kind of stepping stone ritual for hundreds of years.

Like the Stone of Scone, the Stone of Forres is an inspirational, iconic, historical artefact which connects Christianity and Kingship, for everyone to appreciate in the rich history of Scotland.

Appendices:

- Appendix 1) Map of Forres area by Timothy Pont 1593.

- Appendix 2) 19th century photograph of West face.

- Appendix 3) Coronation panel below the Cross, pictured by Digby Mills, 1953

- Appendix 4) Coronation panel below the Cross, sketched by John Borland.

- Appendix 5) 19th century photograph of East face.

- Appendix 6) Mid 18th century sketch of East face, from C McKean, “District of Moray”.

- Appendix 7) Map of 900AD Scotland

- Appendix 8) Lines of sword marks, 2023.

- Appendix 9) Sword marks replicated.

- Appendix 10) Conjectural Map of Medieval Forres.

- Appendix 11) Stone of Forres in its enclosure, present day.

- Appendix 12) Chapelton, the Monks’ Field, looking towards the Chapel

- Appendix 13) Chapelton, the Monks’ Field, looking from the Chapel.

- Appendix 14) Chapelton, an aerial view, with Wright’s Hill and the Monks’ Field.

Sources / Bibliography;

- Robert Douglas, 1934, The Annals of Forres.

- Alfred Houghton Forbes, 1975, Forres a Royal Burgh 1150-1975.

- Alex Fraser, 1996, A Closer Look at Forres of Yesteryear.

- Bruce Bishop, 2007, The Lands and Peoples of Moray.

- HB Mackintosh, 1924, Pilgrimages in Moray.

- Norman Thomson, 2015, A Forres Companion.

- James Miller, 2012, The Gathering Stream.

- Stewart Ross, 1991, Ancient Scotland.

- Elizabeth Sutherland, 1994, In Search of the Picts.

- Sally M. Foster, 2014, Picts, Gaels and Scots, Early Historic Scotland.

- Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans, 2019, The King in the North, The Pictish Realms of Fortriu & Ce.

- Alec Woolf, 2014, From Pictland to Alba, 789-1070.

- Leslie Southwick, 1981, The So Called Sueno’s Stone at Forres.

- David Sellar, 1993, The Sueno’s Stone and Its Interpreters.

- Charles McKean, 1987, The District of Moray.

- Dr James Mackay, 2004, Pocket History of Scotland

- British Newspaper Archives, various publications.

- Dr John Barrett, 1996, Forres 500 Years a Royal Burgh.

- Forres Amenities Association, 1946, Official Guide to Forres.

- Russell and Watson, 1868, Morayshire Described.

- Rev A Wylie, 1886, History of the Scottish Nation.

- WF Skene, 1877, Celtic Scotland.

- Wm Reeves, 1864, the Culdees of the British Isles.

- Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 1940.

- Conor Newman, 2009, The Sword in the Stone.

- Tim Clarkson, 2013, The Makers of Scotland.

- Martin Carver, 2016, Portmahomack, Monastery of the Picts.

Timeline

- 432AD; Death of St Ninian, who brought Christianity to Scotland.

- 563AD; St Columba, with 12 missionaries, arrives in Scotland, establishes Iona as Christian centre.

- 574AD; St Columba takes Stone of Destiny to Iona from Dunadd, for King Aedan’s inauguration.

- 673AD; St Mael Rhuba establishes his mission at Applecross.

- 722AD; St Mael Rhuba dies at the age of 80 years.

- 800AD; St Mael Rhuba’s devotees establish a Culdee Community at Chapelton, Forres.

- 806AD; Iona attacked for a second time, by heathen Norsemen, and 68 monks murdered.

- 810AD; Kenneth MacAlpin born on Iona.

- 839AD; Battle in Fortriu between heathen Norsemen and the Gaels/Picts. Major losses all round.

- 839AD; Alpin becomes King of Dal Riada.

- 841AD; King Alpin dies and is succeeded by his son Kenneth.

- 841AD; Kenneth MacAlpin, Gaelic King of Dal Riada, overcomes the Picts in Fortriu.

- 841AD; Kenneth MacAlpin brings the Stone of Destiny to Scone.

- 841AD; Kenneth MacAlpin eliminates the Pictish King and 7 Earls, at Scone.

- 843AD; Kenneth MacAlpin crowned King of Scots in Scone.

- 844AD: Kenneth MacAlpin commissions the Stone of Forres at Chapelton.

- 850 – 970AD; Kenneth MacAlpin and nine succeeding Kings of Scots, affirmed at the Stone of Forres.

- 1060AD; King Malcolm III sees the Stone on an incursion against the Danes in Moray.

- 1091AD; Stone of Forres falls over during a storm and is covered by soil.

- 1150AD; King David I establishes Abbey at Kinloss.

- 1275AD; Chapel of St Laurence first established on Forres High Street.

- 1275AD; Chapel of St Leonard now within the bounds of new Parish of St Laurence.

- 1296AD; King Edward I of England takes the Stone of Destiny to Westminster Abbey.

- 1303AD; King Edward I visits Kinloss Abbey.

- 1336AD; King Edward III visits Kinloss Abbey.

- 1337AD; Chapel of St Leonard recorded as still in use at Chapelton.

- 1350AD; Black Death kills a quarter of the Scottish population.

- 1456AD; Chapel of St Leonard recorded as still in use at Chapelton.

- 1505AD; King James IV donated money to Chapel of St Leonard.

- 1520AD; Stone of Forres rediscovered after nearly 500 years buried.

- 1527AD; Hector Boece mentions “Sweno” and “Fores” in his first published History of Scotland.

- 1560AD; The Reformation, Catholicism prohibited, Protestantism prevails through John Knox.

- 1562AD; Mary Queen of Scots, and James Stuart (Earl of Moray) visit Kinloss Abbey.

- 1562AD; Mary Queen of Scots covertly funds the re-erection of the Stone of Forres.

- 1567AD; Mary Queen of Scots marries Bothwell, scandalises the nation.

- 1568AD; Mary Queen of Scots defeated, flees to England, and imprisonment.

- 1570AD; James Stuart (Earl of Moray) assassinated by firearm. Plots and counterplots.

- 1574AD; Kinloss Abbey steeple collapses, start of decline of the Abbey buildings and infrastructure.

- 1587AD; Mary Queen of Scots, executed by order of Queen Elizabeth I.

- 1603AD; Union of the Crowns, United Kingdom, English and Scottish under King James I and VI.

- 1612AD; Newly erected (fifth?)Chapel of St Leonard opened at Chapelton.

- 1658AD; Oliver Cromwell’s army takes stones from Kinloss Abbey for Inverness Citadel.

- 1698AD; Culbin estate covered by sandstorm.

- 1700AD -1725AD; Stone of Forres leaning over, made upright by Countess of Moray.

- 1710AD; Jacobite Rebellion, old Pretender, James Stuart, makes bid for crown.

- 1725AD; Alexander Gordon mentions the Stone, and Sueno, in his Itinerarium Septentrionale.

- 1745AD; Jacobite Rebellion, young Pretender, Charles Stuart, makes bid for the crown.

- 1755AD; Rev Lachlan Shaw records how Stone had been “like to fall”, but had been made upright.

- 1837AD; Stone of Forres, conservation area fenced in by metal railing.

- 1926AD; Archaeological excavation confirms 10-ton foundation stone for Stone of Forres.

- 1951AD; Full scale replica made by Edinburgh craftsman John Mackenzie, for Festival of Britain.

- 1965AD; Archaeological survey carried out at Chapelton; findings inconclusive.

- 1991AD; Archaeological excavation, by Rod McCullagh, completed before Stone enclosed with glass.

- 2023AD; Stone of Forres, meaning and purpose, re-appraised.

- 2024AD: Stone of Scone moved from Edinburgh to Perth Museum.